Apr 6, 2020

Telehealth is changing the way clinicians and patients interact

One recent morning, Mary Rowan sat talking with her patients, as she has for two years for her work as a nurse practitioner at Charles River Community Health in Brighton, Mass. – but this time, the visits were over the phone from her one-bedroom apartment.

“I have had only appreciation from my patients about the need to avoid in-person visits given this situation,” Rowan told me. “People are appreciating that we are reaching out and looking out for their safety.”

Rowan is not alone. Amid the coronavirus epidemic, health officials have urged the public to avoid unnecessary visits to doctors’ offices, urgent care clinics and emergency rooms to reduce the risk of contagion.

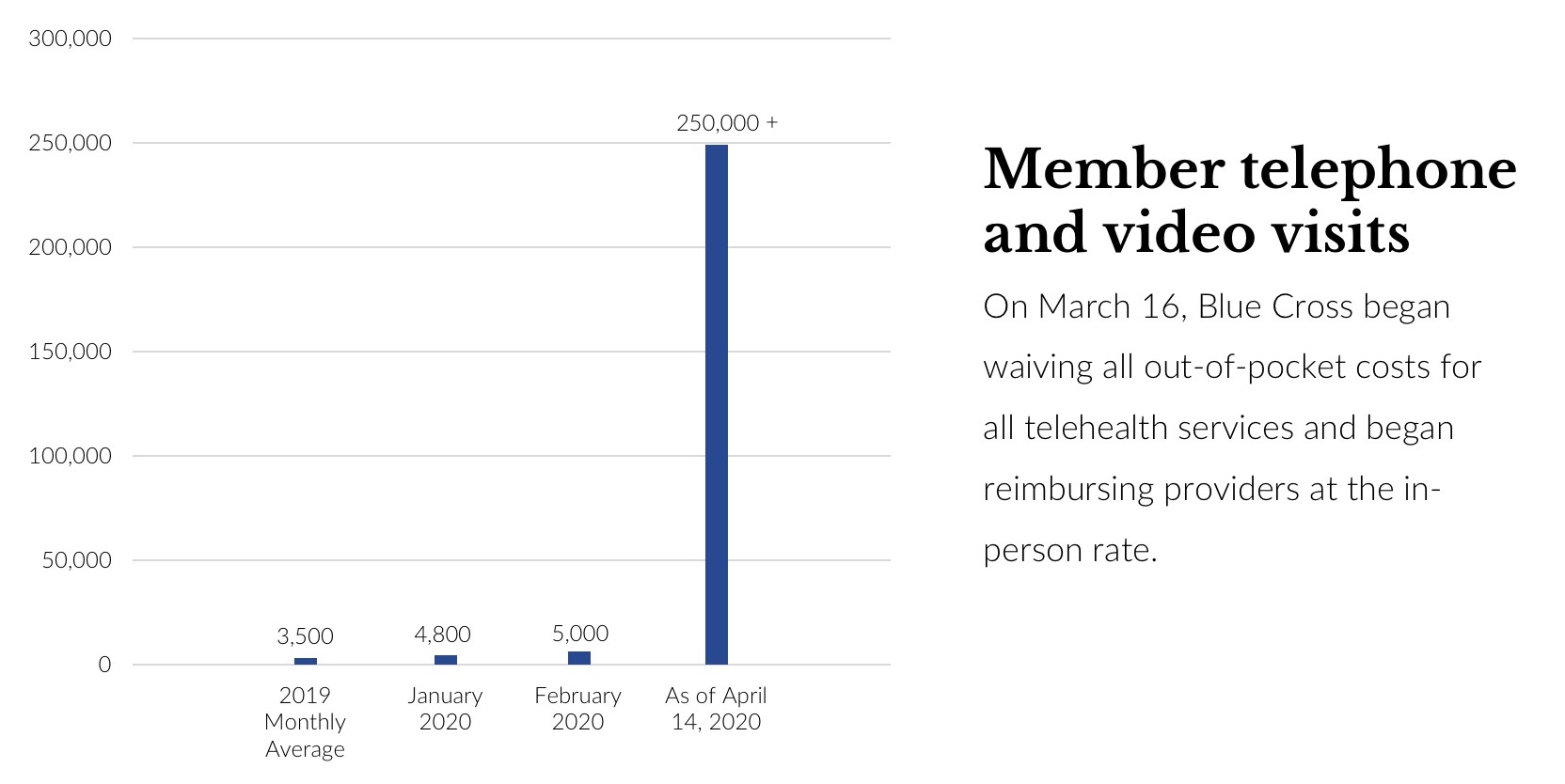

As a result, clinicians increasingly are turning to telehealth – visits by phone or video – to meet with patients. Insurers, including the not-for-profit Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, are waiving all out-of-pocket costs for telehealth, delivered by phone or video for medical and behavioral health needs, for all treatment right now, whether it's coronavirus-related or not. The insurer is reimbursing providers at the same rate for telehealth visits as for in-person visits.

In an indication of the demand, as of April 13 this year, Blue Cross has seen more than 250,000 claims for telehealth since the policy change on March 16, a massive increase over the 2019 average of 3,500 claims monthly.

“To reduce the risk of coronavirus transmission among patients and providers, my clinic has moved almost entirely to telemedicine,” said Dr. Mark Friedberg, senior vice president of performance measurement and improvement at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts and a primary care doctor at Brigham and Women’s Hospital who is now doing his visits remotely from his home office.

“In addition, being telephonic helps us to preserve masks and other equipment for other hospital staff.”

Dr. Mark Friedberg

Rowan says she able to check up on her most vulnerable patients by phone. “I’m asking elderly patients if they can have children go out to the grocery store to reduce exposure. I have a 92-year-old I’m worried about. She has a family member who is still working outside the house and she is potentially being exposed each time that person goes to work. I am telling the family member not to have close contact with his older relative.”

And, she added, “I am also trying to lead by example. I’m trying to educate my patients on minimizing trips outside of the house.”

The next few months will test how well our primary care system can function without the face-to-face visits that have always been the cornerstone of patient care. Once the pandemic subsides and we no longer have to worry about social distancing and viral spread, what lessons can be applied to the future of primary care?

“I think this has the potential to totally shift the delivery model in a way that we have been hoping for a long time. Specifically, we can now really build in virtual care as a normal part of primary care,” said Dr. Salina Bakshi, a primary care doctor who is currently completing a master’s in public health at Harvard School of Public Health. “We have a large opportunity here. I think that one of the hardest things in medicine is changing culture, and this crisis might be exactly what we need to catapult us into the culture change to accept telehealth.”

When Dr. Kim Ariyabuddhiphongs, who practices primary care at BIDMC Healthcare Associates in Boston, had her first virtual clinic last Friday, she found the experience to be more efficient than she expected.

“For established patients, it was surprisingly easy to get through a visit and cover preventive health discussions as well as any new complaints,” she said. “I found the virtual visits were more efficient and took up less time.”

She notes that telehealth visits work best for patients she already knows.

“The established or ongoing relationship is key – I’m very familiar with their medical issues and could easily review their chart while talking with the patient, she said. “Only a subset of patients truly need to come in and touch the health care system beyond the phone call with me. Some patients were up to date with cervical cancer screening and any screening labs and likely won’t need to be seen for at least 1-2 years.”

There are limitations, however. Video allows providers to better evaluate their patients, but not all providers or patients have that capability.

“I am concerned about video visits given that my patient population is primarily low-income recent immigrants from Latin America,” Rowan said. “They may not have the same access to technology needed for video visits as other populations.”

Ariyabuddhiphongs also notes older or more complex patients may need to be seen in person.

“There are certain visits that do require an in-person visit, such as a post-discharge patient that needed an abdominal exam,” she said. “I found that caring for patients with hypertension was challenging because of either a lack of reliability with their home machine and my inability to check the BP myself or have them do 3 sequential readings at rest in the office.”

But for most clinicians and patients, as business and schools shutter to slow the spread of the virus and the public is urged to stay home, telehealth holds enormous promise now – and for the future.

Did you find this article informative?

All Coverage content can be reprinted for free.

Read more here.

PHOTO OF MARY ROWAN BY FAITH NINIVAGGI & PHOTO OF DR. MARK FRIEDBERG BY MIKE GRIMMETT