Apr 6, 2020

The hunt for coronavirus treatments

Since the 1970s, dozens of infectious diseases have been discovered, including SARS, HIV, Ebola, swine flu, Zika – and most recently, COVID-19.

In the arms race against deadly infections, vaccines which prevent viruses, and antivirals – medications that reduce the virus’ ability to multiply – have been key weapons.

To fight COVID-19, which has infected nearly a million worldwide, researchers are working on both fronts, with potential vaccines being tested on a timeline of potential production late this year or next year. And they are racing to develop or repurpose antivirals, which potentially could be deployed far more quickly.

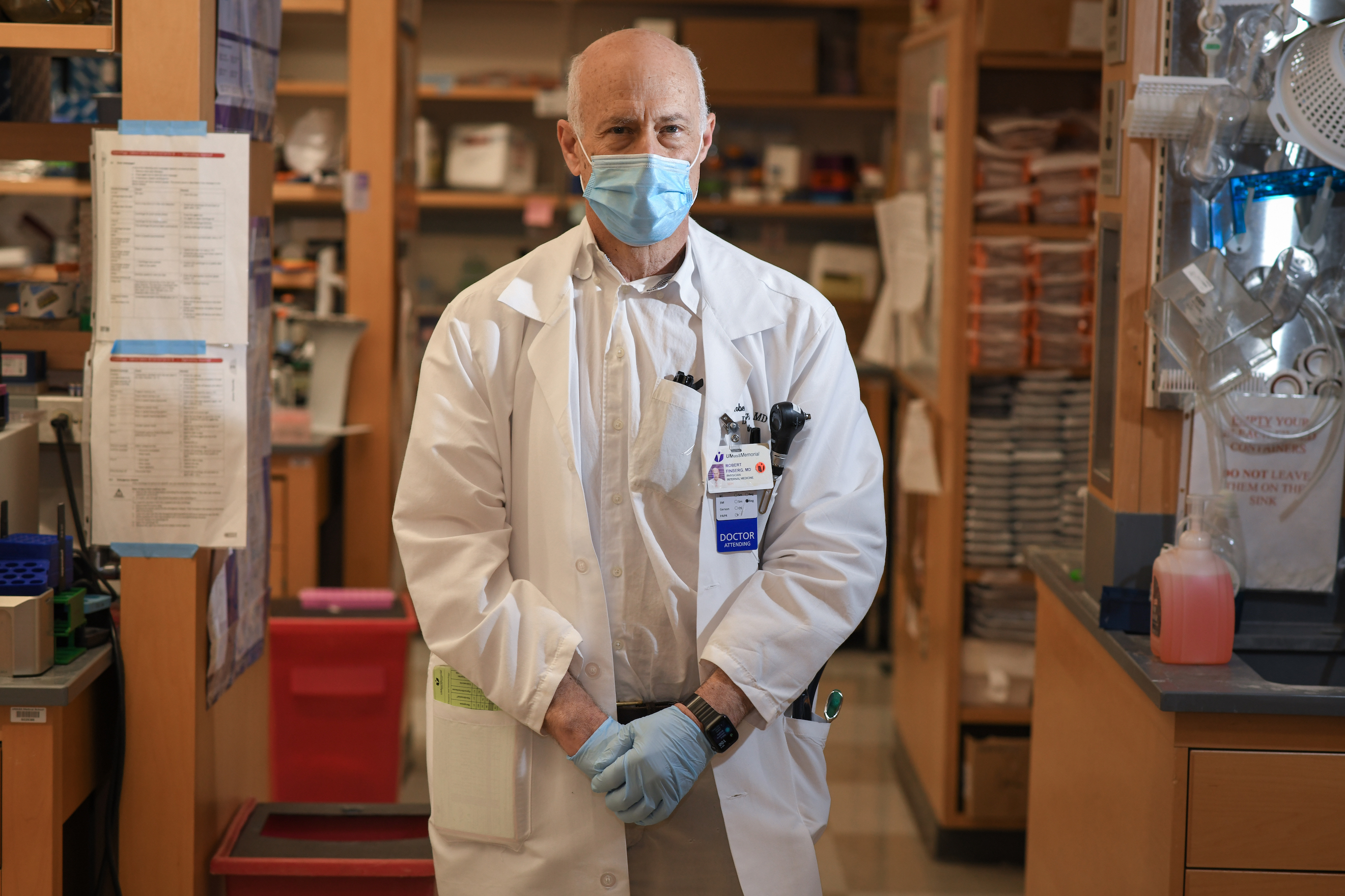

“There are a lot of people researching antivirals, both looking at old compounds and screening for new ways to fight it,” said Dr. Robert Finberg, chair of the Department of Medicine at University of Massachusetts Medical School. “Some antiviral research is focused on taking small compounds and seeing if they have an effect on the virus’ ability to replicate. Some are designed to affect how the virus infects a cell. Others have been used to fight different viruses and researchers are looking at their effect on COVID-19.”

What are antivirals?

Infections are caused by either bacteria, which are are independent organisms, or viruses, which can only multiply within a host organism. Antibiotics act directly on bacteria to inactivate them while antiviral medications interfere with how viruses interact with human cells to reduce viral replication and spread.

While antibiotics were developed for mass use in the late 1930s, antiviral treatments are a much more recent development and did not come into clinical use until the 1960s.

Many antiviral medications interfere with viral infection by blocking certain points of the virus’ replication cycle, such as protease inhibitors for HIV.

Some antivirals block the virus from leaving one cell to infect others, confining the infection to a smaller area, which reduces the severity of the illness and makes it easier for the immune system to kill the virus. Antivirals like Tamiflu treat influenza through this process.

Others work to stimulate the immune system so the body can more easily seek and destroy infected cells, such as interferon for hepatitis C.

How are antivirals developed?

Designing safe and effective antiviral medications comes with daunting challenges – including the crucial fact that viruses use the host's cells to replicate, which makes it difficult to inhibit the virus without harming the cells.

Antiviral development follows FDA guidelines set in place for any type of medication testing: Once researchers find a promising drug, experiments begin to test facets including the best dosage, the most effective way to administer the drug, and potential adverse side effects. If it passes the pre-clinical phase, it moves to trials in humans, of which there are four. Phase I can take several months and studies the maximum tolerable dose, phase II studies efficacy and side effects over the course of about two years, and phase III studies participants in the thousands for up to four years and generally tests the medication against a placebo. Phase IV examines the medication post-marketing – that is, after the product is already on the market.

However, in times of great urgency like outbreaks and pandemics, the FDA fast-tracks these processes. The administration just announced the Coronavirus Treatment Acceleration Program, which ensures speedy responses from the FDA and promises to use “every available method to move new treatments to patients as quickly as possible.”

Using antivirals that have already gone through the approval process for other illnesses, such as HIV or Ebola, also can dramatically speed up the testing process. FDA authorization for the new use can be given within weeks, and physicians can prescribe these medications that have already been produced on a wide scale.

“The protease inhibitors for HIV didn't work with COVID-19, but there are other compounds that have activity against viruses like flu and Ebola. We are unsure how they would work against coronavirus,” Finberg said. “No one has really shown it yet.”

Where does antiviral work on COVID-19 stand?

Because there is so little known about the novel coronavirus, researchers are in the trial and error phase of antiviral discovery and application.

“You see a diversity of responses, from researchers working on blocking viral entry to researchers working on adjusting the host response,” said Dr. Scott Podolsky, professor of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School. “They are also working to reincorporate antivirals studied for viruses like SARS.”

SARS-CoVID-1, the cause of the SARS outbreak in 2003, a closely related coronavirus, shares 79% of its RNA with SARS-CoVID-2, the causative agent of COVID-19.

Some anti-malaria medications, such as chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, are being looked at as possible treatments for COVID-19. These generic drugs currently are commonly used to treat autoimmune disease like rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, as well as malaria. The FDA has issued an emergency authorization to use these drugs to treat COVID 19 and indicated that these drugs should only be used on a short-term, inpatient basis with patients that are seriously ill, as these medications also have the potential for serious and well-known adverse side effects. Research groups, including one at the University of Minnesota, are now studying whether they are effective in novel coronavirus patients.

“The protease inhibitors for HIV didn't work with COVID-19, but there are other compounds that have activity against viruses like flu and Ebola. We are unsure how they would work against coronavirus,” Finberg said. “No one has really tested these compounds in human trials.”

Pharmaceutical company Gilead Sciences, based in California, is expanding access to its antiviral drug remdesivir, which has previously been used to treat Ebola, as an experimental coronavirus treatment. In an open letter March 28, Gilead Chairman and CEO Daniel O’Day said the company was working at “an unprecedented speed” to enroll people in clinical trials. The medication has been provided to more than 1,000 severely ill COVID-19 patients under compassionate use.

“With expanded access, hospitals or physicians can apply for emergency use of remdesivir for multiple severely ill patients at a time,” the letter says. “While it will take some time to build a network of active sites, this approach will ultimately accelerate emergency access for more people.”

Podolsky said all these avenues are reasonable to explore as scientists and biotech firms gather data to find the fastest path to solutions.

“There are so many sick people right now, and people need treatment,” he said. “In the absence of an obvious magic bullet, it’s appropriate to test multiple possibilities.”

Did you find this article informative?

All Coverage content can be reprinted for free.

Read more here.

PHOTOS OF Dr. ROBERT FINBERG & Dr. SCOTT PODOLSKY BY FAITH NINIVAGGI