Sep 27, 2019

Mosquito-borne illnesses on the rise

Cases of the rare and dangerous eastern equine encephalitis virus are ramping up to historic levels across the country, and health experts are urging the public to take precautions.

“There is no way to kill all infected mosquitoes,” said Catherine Brown, epidemiologist for the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, “so it’s very important for people to know how to protect themselves.”

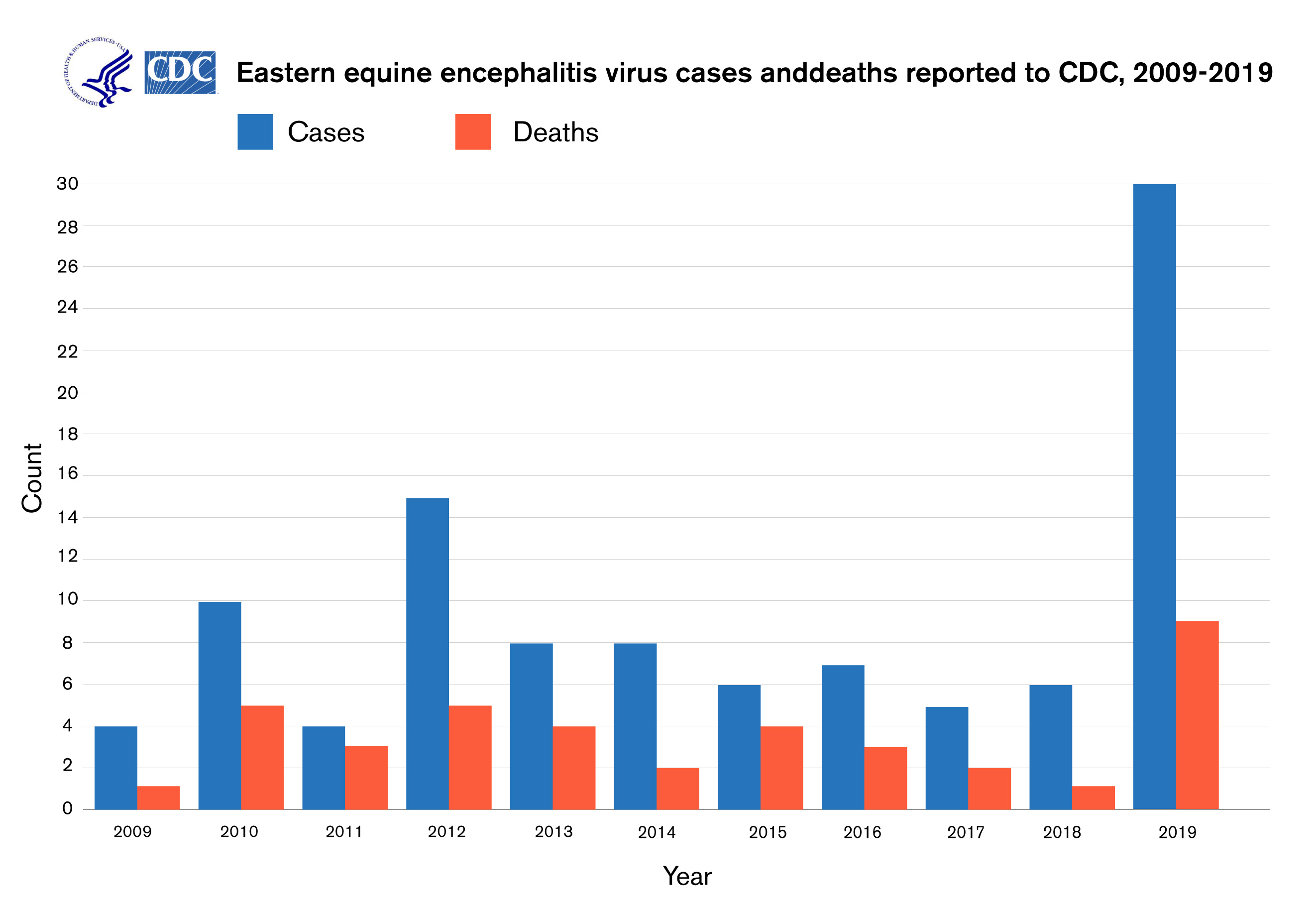

This year, there have been 30 cases of EEE nationally so far, including cases in Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey. Rhode Island, Connecticut, North Carolina and Tennessee. That compares starkly with a national average over the past decade of just seven cases annually, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Eight of 2019’s cases have been deadly, more than double the yearly average of three EEE deaths over the past 10 years.

Massachusetts has seen 10 cases total in the past decade – a number exceeded this year alone. With 12 cases before October, the state is the hardest-hit in the country.

“EEE is a cyclical disease with outbreaks taking place every 10 to 20 years and lasting for two to three years,” said Dr. Tom Hawkins, medical director at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts. “This is an especially bad year.”

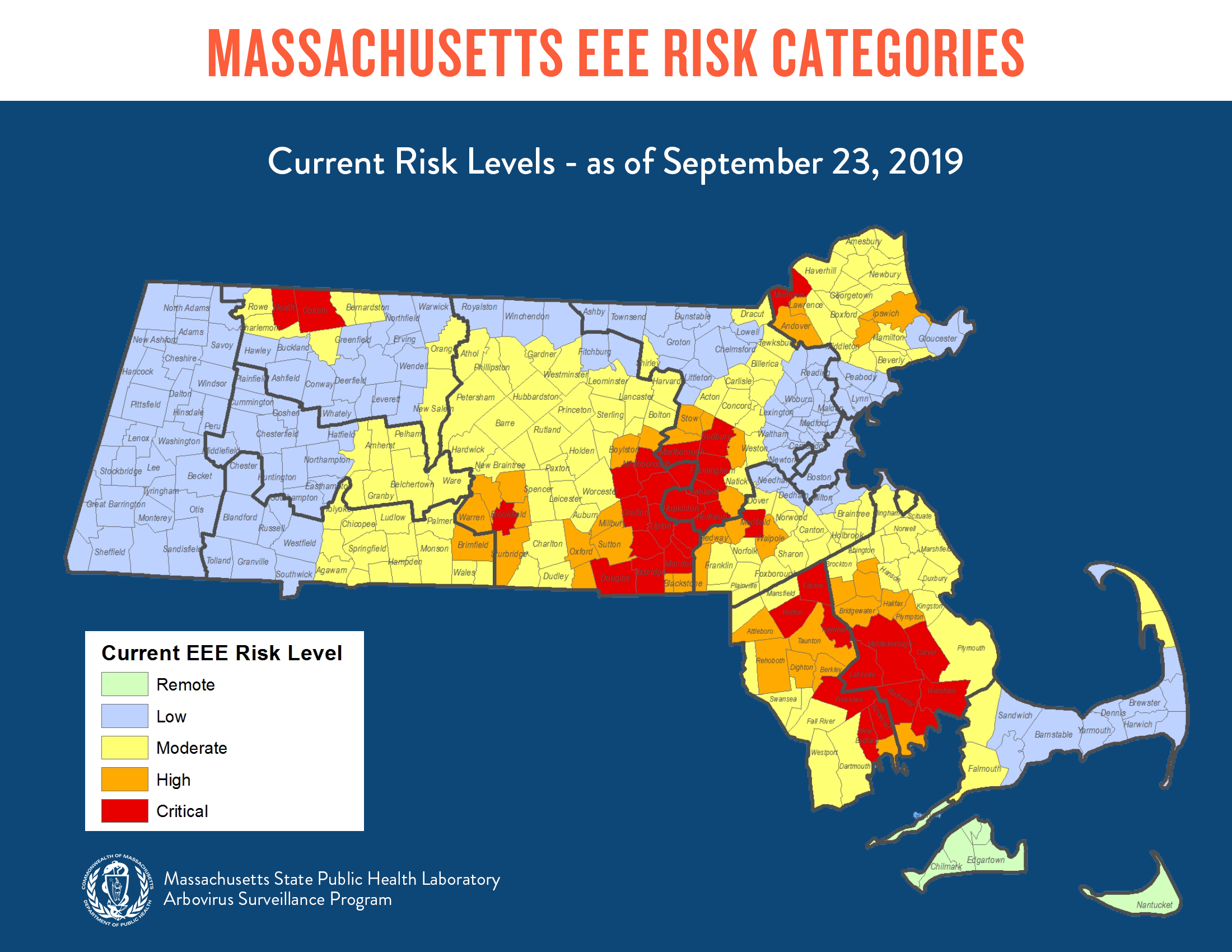

In Massachusetts, state health officials are asking residents to take precautions, especially in the 75 communities at critical or high risk for Triple E.

Those precautions include:

- Cancel outdoor activities between dusk and dawn

- When outside, wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants

- Use insect repellent with EPA registered active ingredients such as DEET. Always apply as directed.

- Drain standing water around your home

- Repair or install screens in your home’s windows and doors

Prevention is crucial because EEE, while rare, is so dangerous. Of the 70 EEE cases in the U.S. in the past 10 years, 30 were fatal.

Hawkins notes that early EEE symptoms can be confused with other illnesses, which may lead to delays in seeing a doctor: the first symptoms may include fever of 103 to 106 degrees, stiff neck, headache, and lack of energy.

The state also confirms that two residents have been infected with West Nile virus, which also is transmitted by mosquitos but is less dangerous and far more common than EEE, affecting hundreds of people across the U.S. during average years.

“There aren’t a lot of treatment options for these diseases,” said Hawkins. "There is no vaccine, no effective treatment. We use antiviral drugs, but they aren’t always effective once these diseases progress."

"There is no vaccine, no effective treatment. We use antiviral drugs, but they aren’t always effective once these diseases progress."

According to Brown, the state epidemiologist, 80 percent of people exposed to West Nile virus typically are unaware of it, while about 20 percent of those exposed may experience a fever, nausea, and feel generally unwell and recover. However, less than 1% will develop a life-threatening neuro-invasive condition that requires hospitalization.

“One person bit by an infected mosquito may see the virus progress to a serious disease while another may never know they’ve been infected,” Hawkins said.

Symptoms of West Nile Virus include fever, headache, body aches, nausea, vomiting, and sometimes swollen lymph glands. Infected patients may also develop a skin rash on the chest, stomach and back.

According to Brown, of the 51 different types of mosquitos in Massachusetts, only three contribute significantly to Triple E or West Nile transmission and the state actively monitors for their presence.

“There is a very robust mosquito surveillance program in Massachusetts,” Brown said. “From early June through November the state department of public health and local mosquito control boards conduct daily trapping and testing of mosquitos to determine the risk of mosquito-borne disease.”

If infected insects are detected, the state and local mosquito control boards can take steps to reduce the risk of human infection through mosquito-awareness campaigns and by spraying insecticides in areas where mosquitos live and breed if the risk of mosquito-transmitted disease is critical or high. The state uses an Environmental Protection Agency-approved insecticide called Anvil 10+10 that does not pose a health risk to humans or an unreasonable risk to birds, and the state notifies residents in advance of its use.

Earlier this month that state conducted aerial spraying in parts of Bristol, Hamden, Hampshire Middlesex, Norfolk, Plymouth and Worcester counties.

“The state is judicious,” said Brown. “Aerial spraying is used when other risk-prevention methods aren’t working.”

The danger of mosquito-borne disease won’t be eliminated for certain until the first hard frost, when standing water where mosquitoes breed freezes. But, experts say, the threat may well be renewed with the warmth of next spring.

PHOTO OF TOM HAWKINS BY MICHAEL GRIMMETT