Apr 27, 2022

When the heroes need help

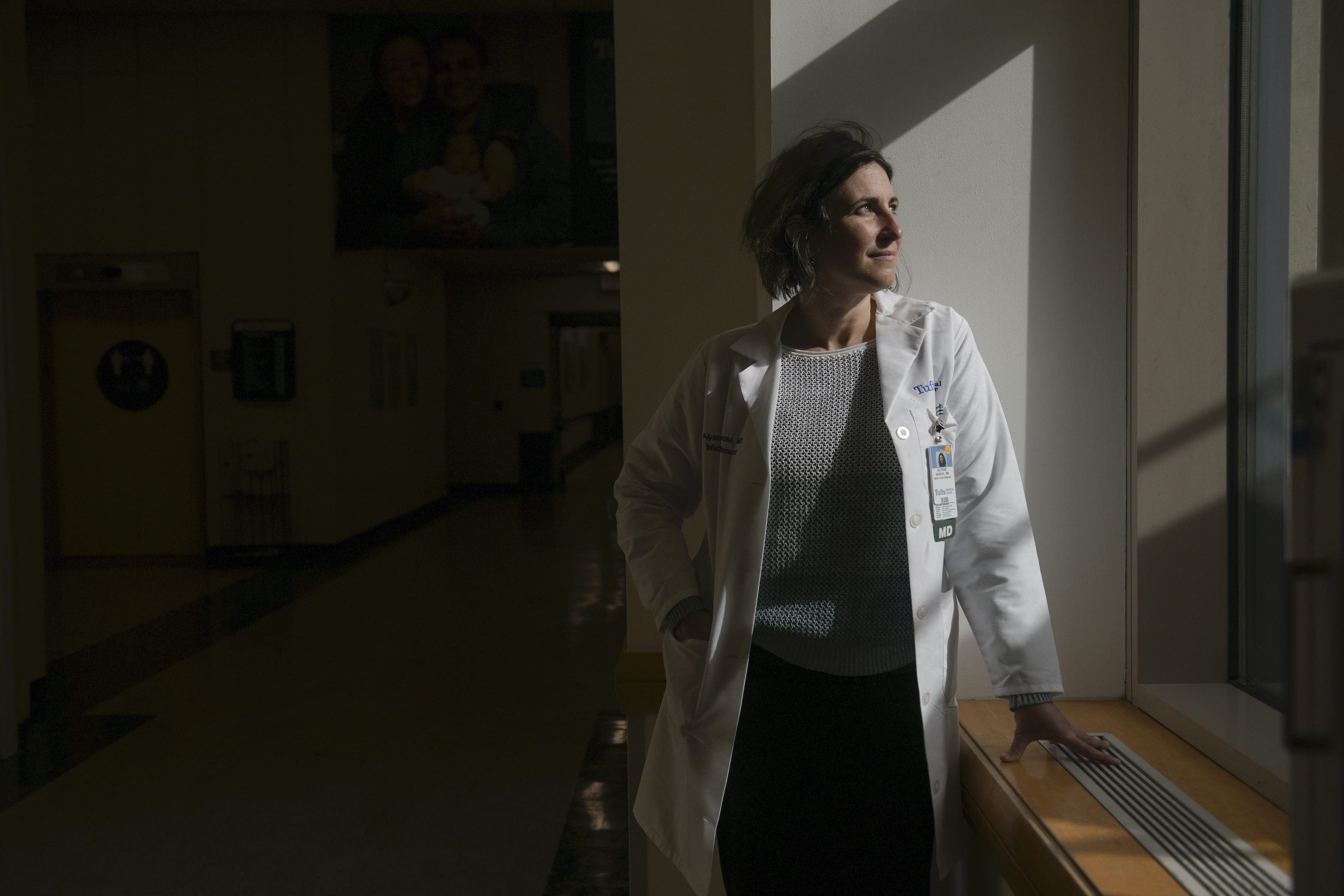

When COVID-19 began raging at full force in March 2020, Dr. Alysse Wurcel had moments when she questioned whether she should be on the front line. “Why am I doing this?” she asked herself. “Why am I putting myself and my family at risk?”

Like many health care professionals, she did it for the same reason she entered the field: She wanted to help heal the sick. But as she worked as an infectious disease doctor at Tufts Medical Center, the relentless illness and death of the pandemic took an enormous toll on Wurcel.

“There's the stress of seeing people die and the endless stream of people coming in. And you didn’t always know who was going to die,” Wurcel recalled. “It wasn’t always the 90-year-old in the nursing facility. Sometimes you’d have a young, healthy person die.”

Some of the cases hit close to home – for example, when she had to watch colleagues become patients, fighting their own personal battles against the virus.

“It is excruciatingly hard, especially when taking care of health care providers,” she said. “You could see yourself in their eyes.”

Wurcel is one of the many health care workers who has sought psychological help to cope with the strain of COVID-19. While that has always been a part of her health routine, she found she needed more support than usual over the past two years. In addition to her heightened job-related stress, she has battled anxiety about taking care of her children during a massive public health crisis.

“I'm someone who has always believed that mental health is a necessary part of my life,” Wurcel said. “But I've reached out more and needed more help since the pandemic hit.”

Longstanding strains

Physicians are often expected to be impervious to stress, and the stigma around seeking mental health care can be intense — but Wurcel is far from alone. A May 2021 study found that out of nearly 21,000 U.S. health care workers surveyed, 61% said they were experiencing significant fear of exposing themselves or their families to COVID-19. Nearly half the workers suffered from burnout, and 38% said they were dealing with anxiety or depression.

The mental health of health care personnel was already in jeopardy even before the pandemic. According to data from 2007 to 2018, women nurses were at twice the risk of dying by suicide as women outside of health care.

Strains for physicians also have intensified over the course of many years, notes Dr. James Colbert, a Newton-Wellesley Hospital internist.

“This was a problem even before the pandemic – physicians were feeling like there were more and more demands placed upon them, and the resources available to them were not necessarily enough to keep up with the demands on their time,” Colbert said. “Then you throw the pandemic on top of it with concerns of keeping safe, not getting COVID, staffing shortages, adapting to telehealth and minimizing in-person interactions, and all of these strains are piling up on top of each other.”

Combating stigma, increasing awareness

The Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation, created by the family of an emergency physician who died by suicide early in the pandemic, has authored and co-authored several national publications expanding the national conversation about physician suicide and the psychological strain on health care workers.

In addition, the group collaborates with members of the health care industry to implement mental health initiatives, and funds research programs that aim to reduce burnout. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts was one of the center’s founding donors.

“We've heard from many groups of individuals who've shared with us the importance of elevating this conversation in the national media, as well as elevating it generally,” said Corey Feist, the foundation’s president and co-founder. “We’ve heard from physicians who saw themselves in Lorna’s story, and mental health professionals who have been able to intervene early.”

Our awareness work has literally been lifesaving.

President Biden this spring signed the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act, which will provide federal funding for mental health education and awareness campaigns geared toward health care workers.

The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care is a Boston-based nonprofit that also focuses on the well-being of health care workers. For example, the center’s Stress First Aid program trains members of health care organizations in identifying stress at work and intervening before staff become overwhelmed, and the Virtual Schwartz Rounds program provides an opportunity for caregivers to share the challenges of their work.

“You can't really understand what people have gone through unless you've gone through it yourself, which is why these programs are so effective – they help facilitate peer and social support,” said Dr. Beth Lown, the chief medical officer of the center, which was founded in 1995 with support from Blue Cross’ leadership. “The need now is greater than ever.”

Managing mental health

The American Medical Association recommends measures to help health care workers manage pandemic stress, including:

- Employing coping strategies like finding respite time between shifts, eating healthy meals on a schedule, engaging in physical activity and staying in touch with family and friends.

- Taking news and social media breaks to reduce exposure to pandemic-related content.

- Performing regular check-ins with yourself to monitor yourself for symptoms of depression and stress disorder, such as prolonged sadness, difficulty sleeping, intrusive memories and/or feelings of hopelessness.

Wurcel notes that social ties can provide key support, but professional help is crucial when struggling with anxiety or depression.

“I think a lot of times we think we can get enough support from our family and friends, and my experience has been that mental health providers give a more objective view and allow for a safe space,” Wurcel said. “I don't know how I could continue to be a clinician without having someone to talk to who's objective. It's a necessary part of my equation.”

Did you find this article informative?

All Coverage content can be reprinted for free.

Read more here.

PHOTOS OF DR. ALYSSE WURCEL BY FAITH NINIVAGGI