Dec 21, 2020

What can our DNA teach us?

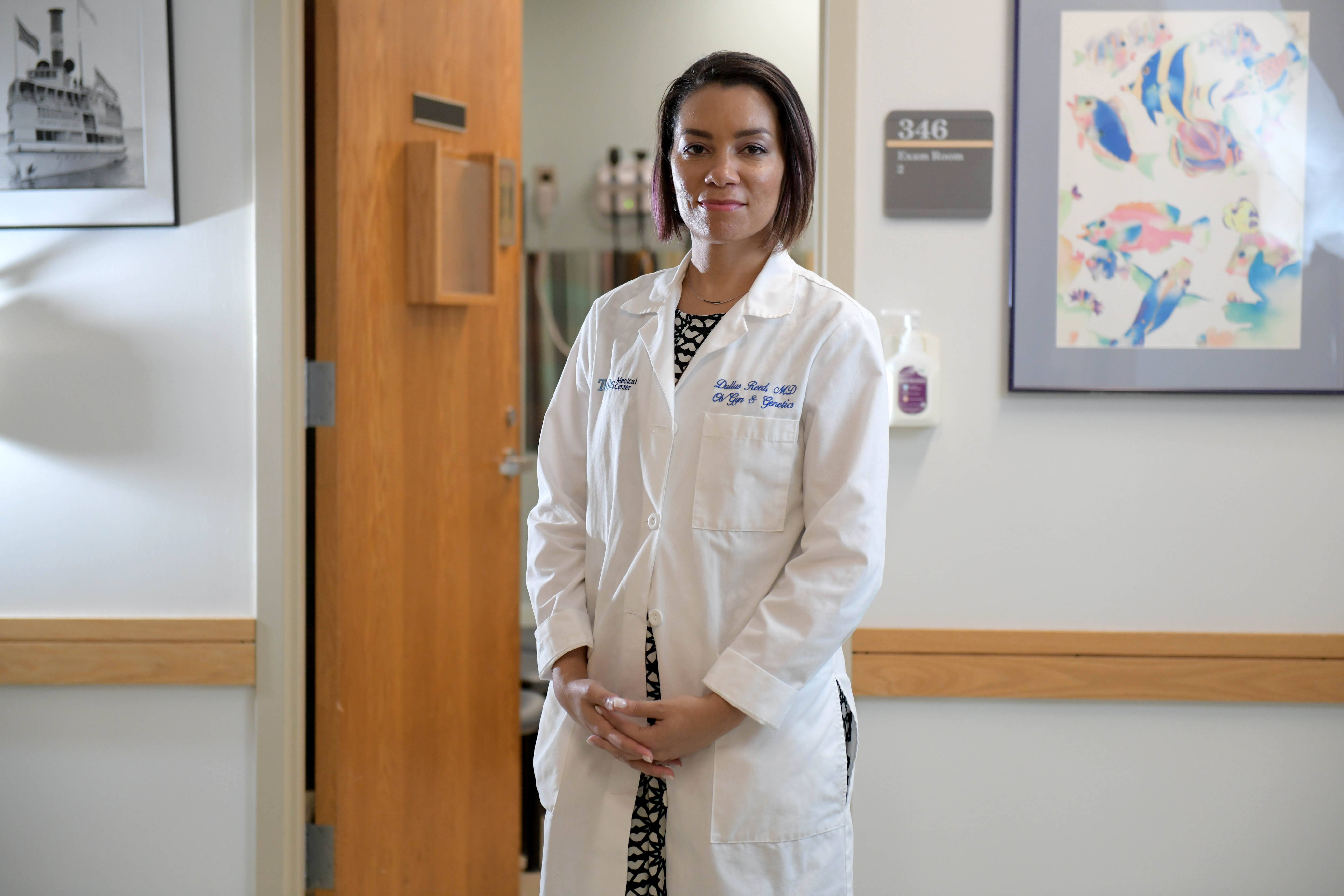

Coverage is proud to publish columns featuring the perspectives of Black women physicians who belong to the Diva Docs network in Greater Boston. Today, Dr. Dallas Reed, assistant professor at Tufts University School of Medicine, division chief of genetics in pediatrics at Tufts Children’s Hospital, director of perinatal genetics and attending physician in the department of OB/GYN at Tufts Medical Center, shares her thoughts with Dr. Philomena Asante, leader of Diva Docs Boston and creator of the Digital Health Award-winning Diva Docs series for Coverage.

My path to medicine was framed by my personal experience. When I was in first grade, my brother was born with a terminal genetic condition called Trisomy 13. He survived for four months, longer than doctors expected.

That’s when I first learned about genetics, which brought me on the path I’m on now.

When I entered Boston University School of Medicine, I was interested in the intersection of obstetrics and prenatal genetics – discovering the genetic causes of anomalies in fetuses. I shadowed genetic counselors and maternal fetal medicine specialists to learn more about the field, and subsequently completed an OB/GYN residency and then a two-year fellowship in medical genetics.

Medical geneticists are like detectives. We look at a patient’s entire history, from the prenatal period to the present day, and try to piece together the mystery of what’s going on. Geneticists work with genetic counselors to help patients understand their condition and options for testing. Geneticists may practice generally or focus on prenatal, cancer, or pediatric genetics, or particular conditions. Some geneticists do research, and some teach medical students, residents, and genetic counseling students.

My mixture of specialties, genetics and obstetrics/gynecology is unique, with only a few people in the world practicing both.

At my hospital, I am the only physician who gets to support a couple through the whole spectrum of obstetrics and genetics care. I may see a couple for preconception counseling to discuss their reproductive genetic risks. When they become pregnant, I follow the pregnancy, counsel about any necessary routine or diagnostic genetic testing, and potentially deliver the baby. If there is a concern about a genetic condition for the newborn, I can evaluate and follow the baby through the neonatal and pediatric period. It is a special job.

I cherish the moments that I get to be the resource that my family once needed.

Historic barriers

It is well known that race is a social construct and not based on biological differences. However, ancestry does impact our genetic code, and can be very important in helping a geneticist make a diagnosis.

Genetic testing is as important for Black patients as anyone else, but historically, Black patients have faced barriers in accessing genetic testing.

First, there have been misconceptions about who may be carriers of certain conditions. For example, the once-held belief that Black women are less likely to carry mutations in high-risk breast cancer genes, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2, led to fewer referrals for genetic counseling and testing.

Second, clinicians may have biases about who they think can afford testing. We strive to ensure cost is never a barrier to genetic testing, and luckily it has become far more affordable in recent years.

Third, for adequate risk assessment, patients need to provide an accurate family medical history. Family relationships are complicated, but for Black Americans, some structural factors add to the complexity. Historically, Black Americans have had less access to good quality health care, leading to a lack of diagnosis, subspecialty referral, and genetic counseling and testing. In addition, decades of policies encouraging mass incarceration, disproportionately affecting Black Americans, means there are a lot of individuals who have been forcibly estranged from their relatives and simply do not know a lot about their family history.

What is the purpose of genetic testing?

A genetic test looks for differences in your DNA, called mutations or variants, that may cause disease. Testing has become increasingly useful in diagnosing genetic conditions since the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003.

Genetic testing helps identify the cause of a condition or determine if an individual is at risk of developing a genetic condition, with the goal of allowing early diagnosis, prevention and better care. As genetic research has evolved, we can even develop personalized treatment for some patients based on their unique genetic variant.

Genetic testing can shed light on a wide range of risks. For example, women with a mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene are at risk of ovarian, pancreatic, and thyroid cancer in addition to breast cancer. Women with a mutation and personal history of breast cancer are at an increased risk of a second breast cancer, as well. Armed with that knowledge, we can recommend increased breast cancer screening, risk-reducing double mastectomy, or medication to reduce breast cancer risk.

We can also learn about family members. For instance, first-degree relatives of women who are positive for a mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene have a 50% chance of having the same mutation, including men, who have an increased risk of prostate, male breast, and pancreatic cancer. Being aware of that predisposition gives those relatives a chance to pursue genetic counseling and testing, and make modifications to their cancer screening, if necessary.

Who is referred for genetic screening?

Genetic testing is not necessary for everyone. For example, only about 5% to 10% of cancers are due to a genetic cause. To determine who is eligible for testing, we look for patterns. A personal or family history of early onset cancer, individuals with multiple types of cancer, those with aggressive cancer types, like triple negative breast cancer, or very rare types of cancer, or those with a high-risk ethnic background, such as being Ashkenazi Jewish, are potentially high risk for a genetic predisposition to cancer.

If you are interested in a genetic test, talk to your primary care physician. They will be able to help coordinate a referral to genetics.

I caution against direct-to-consumer genetic testing (available online or in drugstores) to determine your cancer or other disease risks. Those tests provide limited information and are not always reliable.

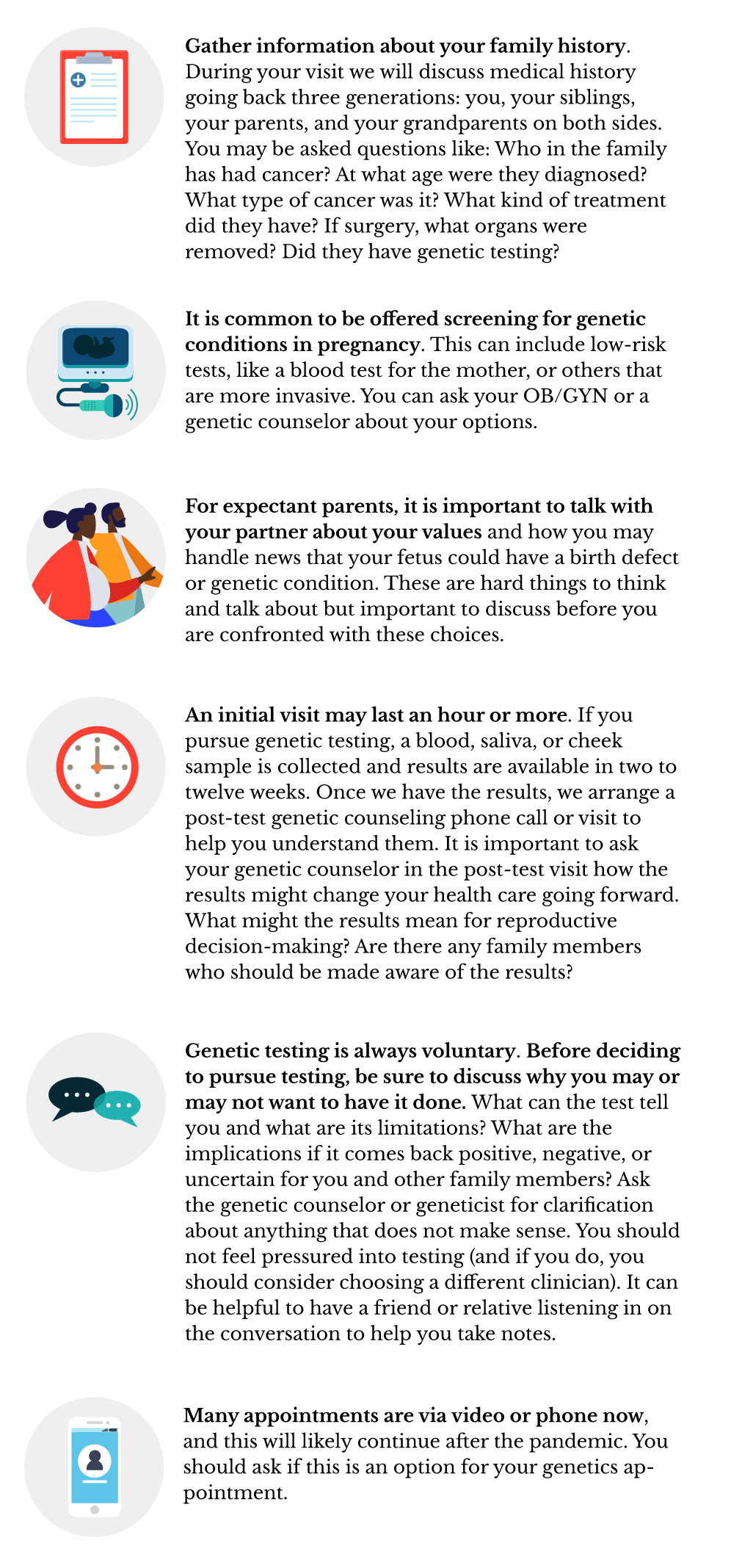

What should you know before your genetic counseling visit?

Why does diversity matter in our field?

Most genetic counselors are white, able-bodied women, and very few geneticists are Black. For a field that involves conversations about very personal histories and values, a lack of diversity affects care. Part of my role on the diversity, inclusion, and equity committee at the American College of Medical Genetics is to consider how undergraduate and graduate medical education, hospitals, and professional medical organizations can increase diversity in the pipeline of genetics providers.

Diversity is important at the most basic level of genetic science too. Genetic testing involves comparing the sequence of chemicals in a patient’s DNA sample to what is considered the “reference sequence,” the expected sequence. But the reference sequence is a compilation of genetic samples from approximately 100 mostly white, healthy European people. That is considered the “norm.” A variant may be considered disease-causing if it is different than the reference sequence, along with other important data the lab uses to interpret the finding. If there is a difference identified and the lab does not have enough information to determine if it is disease-causing, they will call it a “variant of uncertain significance.” In a non-white European individual, there might be more differences identified, and potentially more variants of uncertain significance reported. That becomes an issue when we get the results because it limits our ability to give you, the patient, the answers you are looking for. Diversifying our understanding of common variation due to ancestry would help the field understand more about normal genetic variation.

The NIH-sponsored All of Us research program is enrolling a million individuals of different backgrounds to develop a diverse health database for preventing and treating diseases. The study is also collecting samples for genetic testing, which will diversify what we know about genetic variation.

For a field focused on preventing some of the planet’s most deadly illnesses, this is a tremendously exciting and hopeful time.

PHOTOS OF Dr. DALLAS REED AND Dr. ASANTE BY FAITH NINIVAGGI