Mar 16, 2020

Saving lives by staying home

Gov. Charlie Baker’s closures of the state’s school districts, limits on restaurants and other businesses and other “social distancing” measures are crucial to slowing the spread of the coronavirus, clinicians say, pointing to decades of medical evidence.

“Let’s look at the reality that this virus is already here and spreading and dangerous. Would you prioritize doing something that might put yourself or your family in a situation where you might get sick?” asked Dr. Jamie Colbert, hospitalist at Newton Wellesley Hospital and senior medical director at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts. “I’m not willing to take that risk for myself or my family.”

Joining mayors and governors across the country, Baker ordered public and private schools across Massachusetts to close until May 4, ordered non-essential businesses to close their doors and operate only remotely, limited restaurants to only takeout and delivery, and banned public gatherings of more than 10 people, including in gyms, theaters and churches. Grocery stores and pharmacies are exempted.

Residents are urged to stay home as much as possible and to avoid unnecessary travel and unnecessary person-to-person contact -- the state specifically notes parents should not arrange playdates, and sports games should be canceled, along with non-essential medical care like eye exams, teeth cleaning and elective procedures. The MBTA is cutting back on service, and in Boston, Mayor Martin J. Walsh has ordered a halt to major business and city construction projects.

“This is a time of shared sacrifice,” Boston Mayor Martin J. Walsh said after the announcement of the measures. “It will save lives.”

Two paths

The virus, which causes mild flu-like symptoms in most but leads to critical illness and death in some, has now reached the pandemic stage, meaning worldwide spread is inevitable, according to the World Health Organization. Containment – limiting it to a particular region – is no longer possible. There is no natural human immunity, no vaccine and no antiviral treatment.

It is possible to slow the infection rate, protecting our health care system from being devastated by a tsunami of COVID-19 cases that in turn infect health care workers and prevent other patients from getting the care they need.

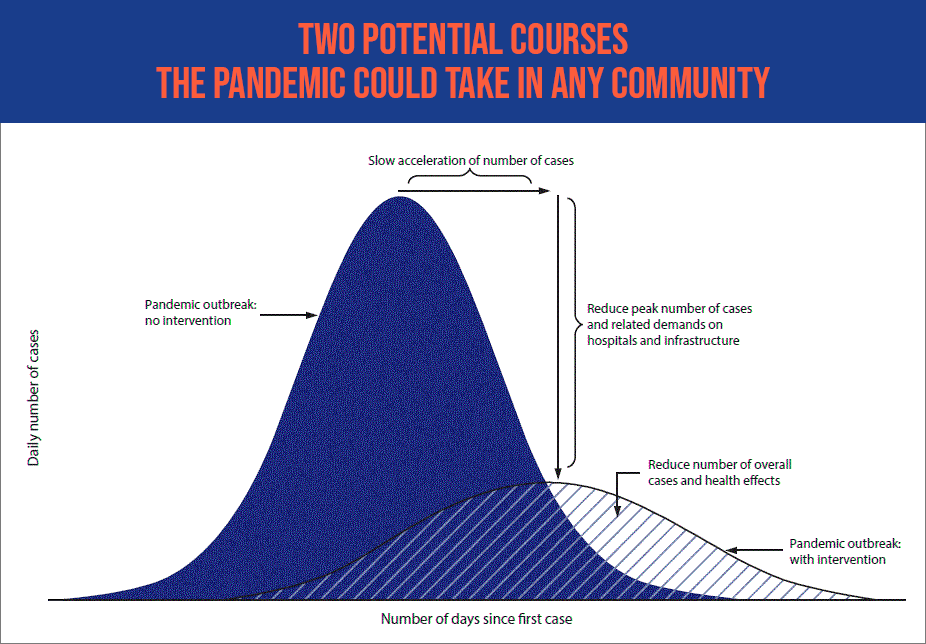

Epidemiologists use a simple graphic below to illustrate the two potential courses the pandemic could take in any community: social distancing measures can create a slow, gradual “curve” of cases, spread over a long period of time, which can be adequately cared for within our health system’s capacity. Doing nothing, on the other hand, can result in a giant spike of infections that overwhelm hospitals, sicken health care workers and result in fewer people getting the care they desperately need.

“It’s about reducing the number of people who get infected at any given time, because it’s much easier for our health care system to take care of the same number of patients if they are spread out over time,” Colbert said.

Italy, where there were few social distancing measures taken during the early days of the pandemic, provides a cautionary tale for the U.S., Colbert said.

“The big issue in Italy right now is that they don’t have enough ICU beds or ventilators to care for the massive influx of critically ill patients, so they have had to ration health care services and support, meaning that they are providing services and equipment to those who have the best chance of survival,” Colbert said. “We don’t know how the coronavirus outbreak will play out in the U.S., but if we have a rapid spike in the number of cases, there is a possibility we won’t have enough doctors, nurses, hospital beds, ICU beds or ventilators to care for the surge of patients.”

What can we do?

What can we personally do to flatten the curve and slow the spread of the virus? Colbert says steps include many of the common-sense actions we have already heard about:

- Physical distancing (also known as “social distancing”): Avoid physical contact with people or objects that might pass the infection to you—and to others you might encounter later. Work from home if you are able; limit the use of public transportation, especially during peak hours; cancel or avoid large gatherings and unnecessary travel. Cancel children’s playdates, parties and sleepovers, as well as adults’ visits to friends and relatives’ houses and apartments. (Physicians note people who have coronavirus can transmit it before they feel unwell.) Limit your trips to stores, restaurants and coffee shops, and wash your hands thoroughly before and after. Don’t shake hands.

Baker had a special message for parents: "This means no free-for-all playdates and more time at home with only immediate family for the next three weeks."

- Avoid hospitals and doctor’s offices if you are healthy. Baker has directed hospitals to postpone elective surgeries. Cancel well visits, or call your doctor to discuss using a telehealth platform. You also can call Blue Cross' nurse-staffed 24/7 help line at 888-247-2583.

- If you are sick, stay home, and contact your doctor (in an emergency, of course, call 911). If you have questions about coronavirus testing, in Massachusetts, you can call the Massachusetts Department of Public Health at 617-983-6800. Health insurers have set up hotlines for questions about coronavirus as well. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts’ is 888-372-1970. For members concerned about any other health issue, Blue Cross also offers a free line staffed by nurses 24/7: 888-247-2583.

- Personal hygiene, such as washing your hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds; avoiding touching your eyes, nose and mouth; covering your cough or sneeze with a tissue or the crook of your elbow instead of your hand; and cleaning commonly used surfaces.

One clinician’s insights

What history teaches us

The influenza pandemic of 1918-1919, the most deadly contagious illness in human history, killed approximately 40 million people worldwide, researchers note. It left behind rich data depicting the ways communities responded.

Cities that implemented social distancing measures earlier “had greater delays in reaching peak mortality, lower peak mortality rates, and lower total mortality,” a JAMA review found.

Days mattered: “Early implementation of certain interventions, including closure of schools, churches, and theaters, was associated with lower peak death rates.”

The historical record is filled with vivid warnings.

For example, the first cases of disease were reported in Philadelphia on Sept. 17, 1918, but “authorities downplayed their significance and allowed large public gatherings, notably a city-wide parade on Sept. 28, 1918, to continue,” a National Academy of Science review relates. “School closures, bans on public gatherings, and other social distancing interventions were not implemented until Oct. 3, when disease spread had already begun to overwhelm local medical and public health resources.”

In St. Louis, Mo., on the other hand, the first cases were reported Oct. 5, and authorities rapidly implemented social distancing measures by Oct. 7.

Philadelphia ended up with a death rate more than eight times the rate in St. Louis.

“If you look at the curves of outbreaks, they go up in big peaks, and then come down. What we need to do is flatten that down,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told reporters recently. “That would have less people infected. That would ultimately have less deaths. You do that by trying to interfere with the natural flow of the outbreak.”

Did you find this article informative?

All Coverage content can be reprinted for free.

Read more here.

PHOTO OF Dr. JAMIE COLBERT BY MIKE GRIMMETT