Jun 12, 2023

Resilience 101

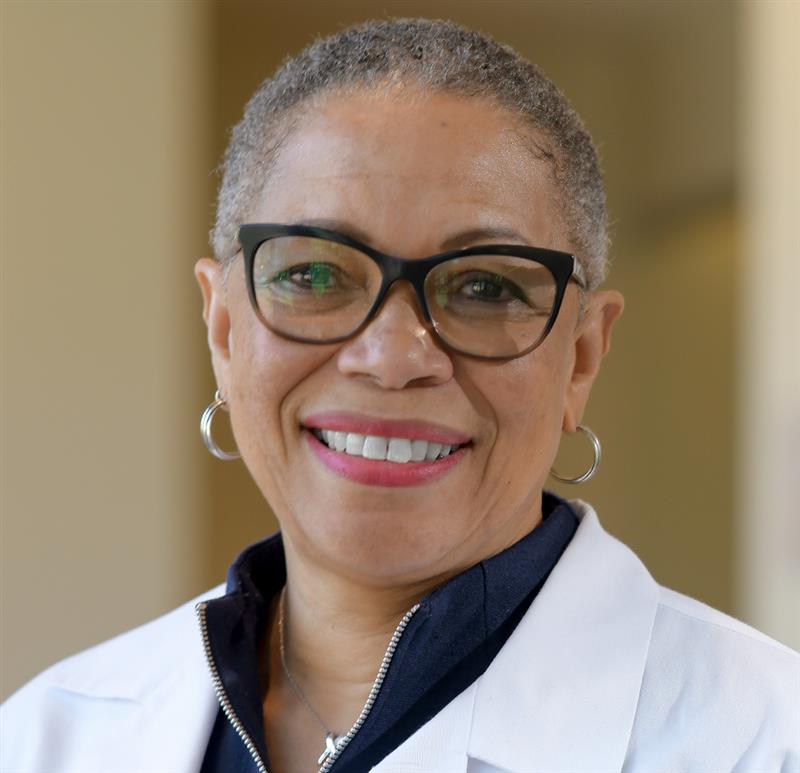

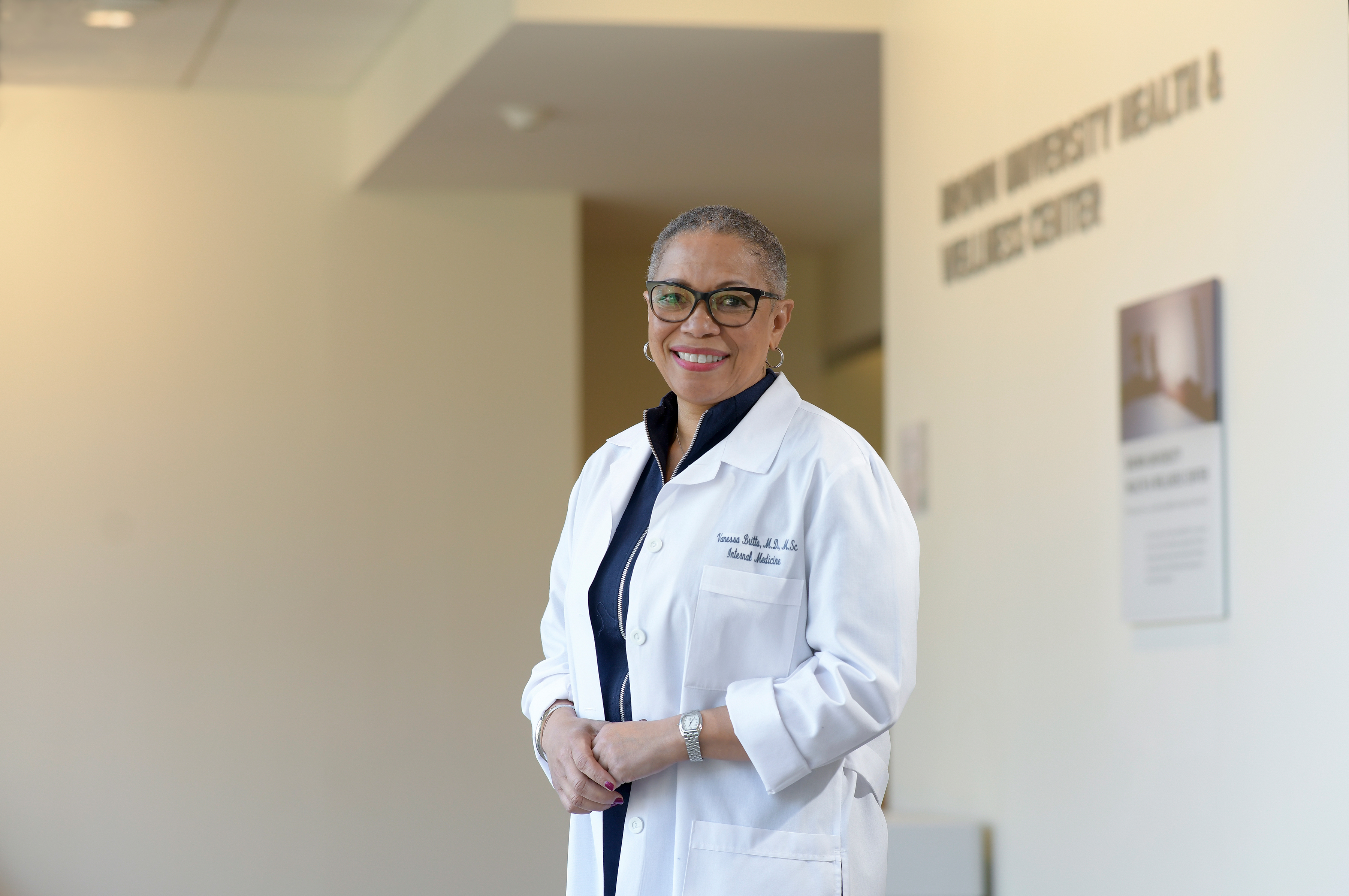

Coverage is proud to publish columns featuring the perspectives of Black women physicians who belong to the Diva Docs network in Greater Boston. Today, Dr. Vanessa Britto — an internist and assistant professor of medicine, associate vice president for campus life and executive director of health and wellness at Brown University — shares her thoughts with Dr. Philomena Asante, founder of The Diva Docs Black Women MD Network, creator of the award-winning Diva Docs series for Coverage, and the incoming physician chief of student medicine at Yale University/Yale Health.

I am a Cape Verdean American, born in Southeastern Massachusetts to parents who understood the power of education.

My mother and father were first-generation, born to immigrants, and didn’t have the opportunity to graduate high school before going to work. When she was still a teenager, my mom went to Boston to work for affluent families as a domestic.

As a housekeeper, she watched what she described as the “madame”, the woman of the house, curate her children’s lives. Best of schools, music lessons, dance lessons, all the things that went into those children going on to achieve a certain modicum of success. Later in my life, she recalled that period and told me, “You know, I thought about what I saw and wondered what would happen if I did some of those same things?”

By the time I came along, the youngest child, my dad was a welder and my mom had gone to hairdressing school and become a small business owner. I took piano lessons, I took dance lessons, I did all of those things that she’d seen. She and my dad gave me a sense that the world was really mine.

I loved school and did well. My high school science teachers told my parents, “She has an aptitude. If she has any interest, steer her toward medicine.” When it was time for me to go off to college, I went to Dartmouth College and loved it.

At first, though, I was very intimidated. I was a public school, first gen kid, and suddenly I was among kids who had gone to private schools their whole lives. I didn’t feel as though I could compete.

But then I started spending a lot of time at Mass Eye and Ear with my dad who had glaucoma and was legally blind. I watched his physicians and kept thinking, “They are doing what I really want to do!” I had found my path.

After I graduated from medical school, I went to Brown, which had the premiere primary care internal medicine program in the country. That program truly taught me to treat the whole patient, to recognize and center their social determinants of health. In part, that’s what drew me to come back to Brown as executive director of health and wellness, after many years building a women’s health practice and then directing health services at Stonehill College and Wellesley College.

What does a student health center do?

As executive director of Brown’s health and wellness services, I oversee five areas with a staff of about 200: health services, counseling, emergency medical services, health promotion and student accessibility services. They all work as a team – using an integrated model – to meet students’ needs.

We have primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, and clinicians, a lab, X-ray, and full pharmacy. On the counseling side, we have a strong team of psychotherapists and psychiatrists, a psychiatry resident.

Our robust health promotion team supports a social justice model including, for example, advocating for students who have been harmed as a result of interpersonal violence. We address the full arc of care, from prevention all the way through to crisis.

We support and care for all 10,000 undergrads, graduates, and medical students. We have traditional-age students as well as returning students, some in their 50s or 60s. All enrolled students have access to all our services, seven days a week, morning to night, with no fee or copay.

What I say to students is, “There’s no wrong door. If you come in and you don’t quite know what you need or where you should go, we’ll help you.”

Why is a college health service important?

For many students, particularly international students or students who come from under-resourced communities, a college health service may be the only health care available to them.

We aim to present students with opportunities to be cared for but, most importantly, learn how to care for themselves.

We help them develop life skills — for example, how to navigate the health care system, how insurance works, why nutrition, fitness and sleep are important. All of it is just as important as academics.

Of course, it is critically important for our work to be connected to the work of our campus partners on the “academic side of the house." Those of us who are in this field know that students can’t engage with their studies unless they’re healthy. The mind and body are one, in a foundational way.

What are some of the key health challenges for students in 2023?

College students often experience elevated levels of stress related to changes in lifestyle, academic workload and new relationships. During the pandemic in particular, we’ve seen those strains manifest in increasing mental health issues.

The Healthy Minds Study, which collects data from 373 campuses nationwide, found more than 60% of college students met criteria for at least one mental health problem, including anxiety, depression, eating disorders and substance use.

We have resources to support our students: For example, for a student who is challenged with an eating disorder, we can help assemble a team — a clinician, a therapist or psychiatrist and a nutritionist — and if necessary, refer the student to intensive outpatient therapy. Most importantly, we can help students find balance and recognize when it’s time to take a break and focus on well-being.

We also help students feel socially connected. Having meaningful peer connection is so important, whether on a team or a student group or in any number of ways. Students need to look out for each other, build community, and feel like they have a sense of connection to other people and that they matter.

Sexual and reproductive health care also is important. We provide IUD and other long-acting, reversible contraceptives. We screen for sexually transmitted infections, including most recently monkeypox. We also provide trans health care. Additionally, we develop specialized care plans for students who have serious, chronic illnesses who need support and team-based care over time. We think deeply about the needs of our students and try to make their experience with health care as frictionless as it can possibly be.

We know that students learn best from each other, so we have a network of peer health educator programs supported by our health promotion team. We aim for the representation in those programs to be broad and inclusive of all students – undergrads, grads, international, returning, etc.

We also work closely with the parent and family engagement office at the division of campus life, to help parents prepare their students for the transition to becoming advocates for their own physical and mental health.

Overcoming barriers to care

In the U.S., we see racial and ethnic disparities in a range of health conditions, stemming from barriers to care with deep roots in structural racism.

And we know college students who are dealing with food insecurity or financial strain may experience more need for care and increased barriers to accessing it.

Stressors experienced by students of color – particularly those who are low-income or first-generation — can go untreated at a disproportionate rate, with significant impacts on health and wellbeing.

We can help address these disparities.

To start, it’s important for student health centers and counseling centers to work toward being as diverse as possible, so students can see themselves in their health care providers.

It’s also important to lead with cultural humility. We need to listen, to put ourselves in our students’ shoes. We have to recognize it’s intimidating to be in an environment of power and privilege. Students may be unsure whether their insurance covers their care, whether they will be understood, whether their privacy will be respected, whether a visit to a health service could affect them academically. It’s important for us to be aware of those concerns, to listen and address them.

And it’s important for college health care providers to get out into the college community, do outreach, show up where the students are, so they see us and we’re familiar to them. Students want to know that we get them, we understand them.

How can a college health center help prepare students for the ‘real world’?

Part of our mission is giving students the life skills they will need when they leave us. What do students need to know to take care of themselves? What do they need to know to take care of their families? Beyond healthy sleeping and eating and fitness habits, how can they prepare for the big disappointments in life?

We think about the professional challenges they will face, even the most gifted students and how to prepare for those: “There are going to be times when you’re going to work incredibly hard, and you’re still not going to get the job or the grant or the promotion. That doesn’t mean that you’re a terrible person or that your life is now a shambles.”

We think about the big question: How do you build resilience into students’ live — into their well-being?

We can help students – and parents and faculty -- understand the importance of connection, the importance of resilience, the importance of grace, the importance of perspective. Teaching those core values will help them later in life. Without those values, we, as a culture, struggle.

It's such a powerful opportunity to show up, at a time in our students’ lives when we can really make a difference.

PHOTOS BY FAITH NINIVAGGI