May 21, 2021

‘If a free taco can help get people vaccinated, well, that’s wonderful’

“You know what, I love this.”

At that moment, a tear came to Dr. Matilde “Mattie” Castiel’s eye. Her voice cracked. Worcester’s commissioner of health and human services sat on a folding chair in the parking lot of Taco Caliente, watching a cross-section of neighbors and strangers roll up their sleeves to receive their first dose of what she called “the equity vaccine.”

“I love this because people just don’t understand the importance of getting the vaccine,” she said, emotion nearly choking off her words, “but if I can go out into the community and talk to people,” she said, catching her breath, “that’s huge.”

Mattie Castiel had jumped out of a van that ferried her from a construction site across town where she’d just overseen a vaccine delivery to workers there

Taco Caliente was one of nearly a dozen “pop up” or microclinics across the east side of Worcester, designed to bring COVID-19 vaccines to what might otherwise be a forgotten population in one of the Massachusetts cities that has been hardest-hit by COVID-19.

“The loss of life and suffering from COVID-19 has been profound, with a disproportionate impact in communities already bearing a disproportionate burden of illness and disease,” said state Department of Public Health Commissioner Dr. Monica Bharel, whose department has led the state vaccine equity initiative which has brought vaccine education canvassers to 82,000 doors and hosted nearly 500 local events in the state’s 20 hardest-hit areas, including Worcester. "These programs are what we need now, bringing vaccination to where people are and enabling everyone to have access to the vaccine.”

Today in Worcester, Castiel said, “the goal is outreach, pure and simple, to get people of color vaccinated. Yes, there’s been a history of reluctance and fear about vaccines among communities of color. While that is certainly true, I believe the greater problem is one of access more than fear or skepticism.

“People here simply can’t afford to leave their jobs, their kids. That’s why we have to come to them, go to their job sites, if possible, churches, stores, barber shops.

“And if a free taco can help get people vaccinated, well, that’s wonderful. It’s what the equity vaccine push is all about. “

COVID, Castiel said, has managed to exacerbate inequities that have long existed in health care, with people of color suffering disproportionate rates of infection, hospitalization and death. In doing so, she explained, it has also forced a kind of MASH approach to the delivery of critical tools to combat the pandemic, just as the Army brings mobile surgical units to areas of combat. Simply put: you bring equity to the vaccination process by meeting people where they live and work.

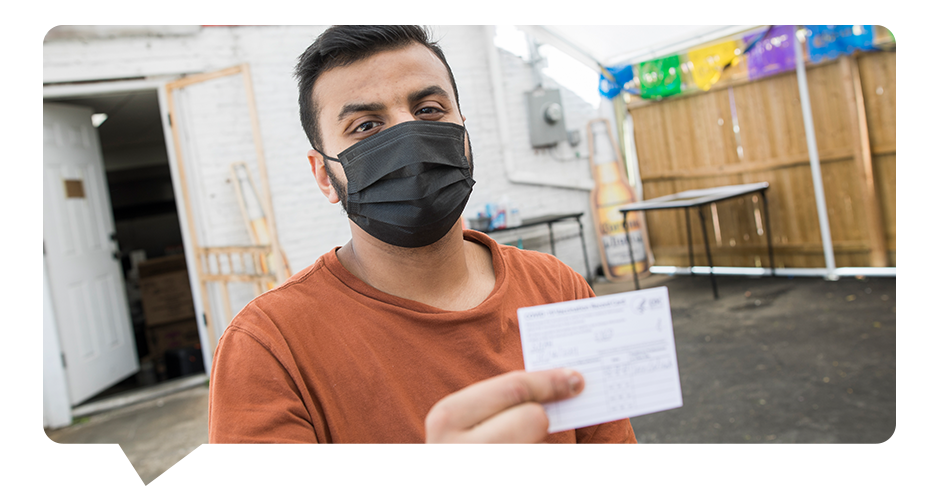

Case in point: Carlos Rosario, a 39-year-old barber and father of four, who explained through a translator that he wasn’t actively seeking the vaccine because he couldn’t afford to take time off from work.

“In the beginning,” he said, “the lines were so long to get a shot and I couldn’t afford to wait. I didn’t really think about it, but it feels good now,” he said as an expansive smile lit up his face.

By day, Syed Shah, 20, manages a Crown Fried chicken outlet a few blocks down Chandler Street from Taco Caliente. At night, he takes classes at Clark University.

“I set up an appointment to get the shot, but I waited and waited,” he said. “I was quite nervous because I have an immune system disorder.”

He arrived at Taco Caliente with his brother and the owner of Crown Fried Chicken. All three were vaccinated. “Now I feel much less nervous, thank you.”

For Deborah Beilen, 52, getting her shot of the Pfizer vaccine seemed more a point-of-purchase impulse buy as she and her girlfriend drove by Taco Caliente.

“I don’t know,” she sighed, “I’m still reluctant. I mean, where are these vaccines made? I don’t know. I just happened to be driving by with my girlfriend and saw the “Free Clinic” sign. So, I figured, why not.”

Kristin Sullivan said she waited months for a shot while supplies were limited, and when she finally got her appointment, she gave it to her elderly parents.

“I just felt it was more important to see that my parents were protected,” the 37-year-old nursing student said. “I had faith that things would work out. I never imagined I would get vaccinated in a taco stand,” she laughed. “But then growing up right here in the city, this really makes perfect sense to me.”

Vaccination is free and is now widely available to anyone who lives, works or studies in Massachusetts, with no ID or insurance required. The state’s largest not-for-profit health plan, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, is providing free transportation options.

As Mattie Castiel sat at one of the picnic tables in the driveway of Taco Caliente, a local shelter worker passing by after vaccination placed his hands on the 66-year-old doctor’s shoulders.

“Want you to know,” he said, “this is my second mother right here.”

Mattie Castiel touched his hands and smiled. It was not the smile of a health & human services commissioner, but more the nurturing smile of a beloved family member.

It was also the smile of gratitude from a woman who emigrated from Cuba in 1962 at the age of 7 as part of what was known as Operation Peter Pan. She was raised and schooled in California because it was thought she was allergic to the cold.

“But here I am,” she says, “so go figure.” Truth is, this immigrant has settled where she is most needed and a city is most grateful.

There is something almost apostolic about Mattie Castiel’s desire to get the Covid vaccines to those most in need.

Health care is not political. It’s all about reaching out to people, to give them the access to all those things that make life better.

- Mattie Castiel said

On a recent Monday afternoon, in the east side of Worcester, the very best part of health care could be found in that sacred space otherwise known as the parking lot of Taco Caliente.

PHOTOS BY NICOLAUS CZARNECKI, WHO WAS VACCINATED AT THE TAQUERIA