Feb 23, 2020

Life before vaccines: Smallpox

Vaccination is one of the greatest advancements in public health, saving hundreds of millions of lives in the past century.

But ironically, the very success of vaccination has given some a case of historical amnesia, doctors say. Rising, unfounded skepticism about the benefits of vaccines have led to outbreaks of once-rare diseases in recent years.

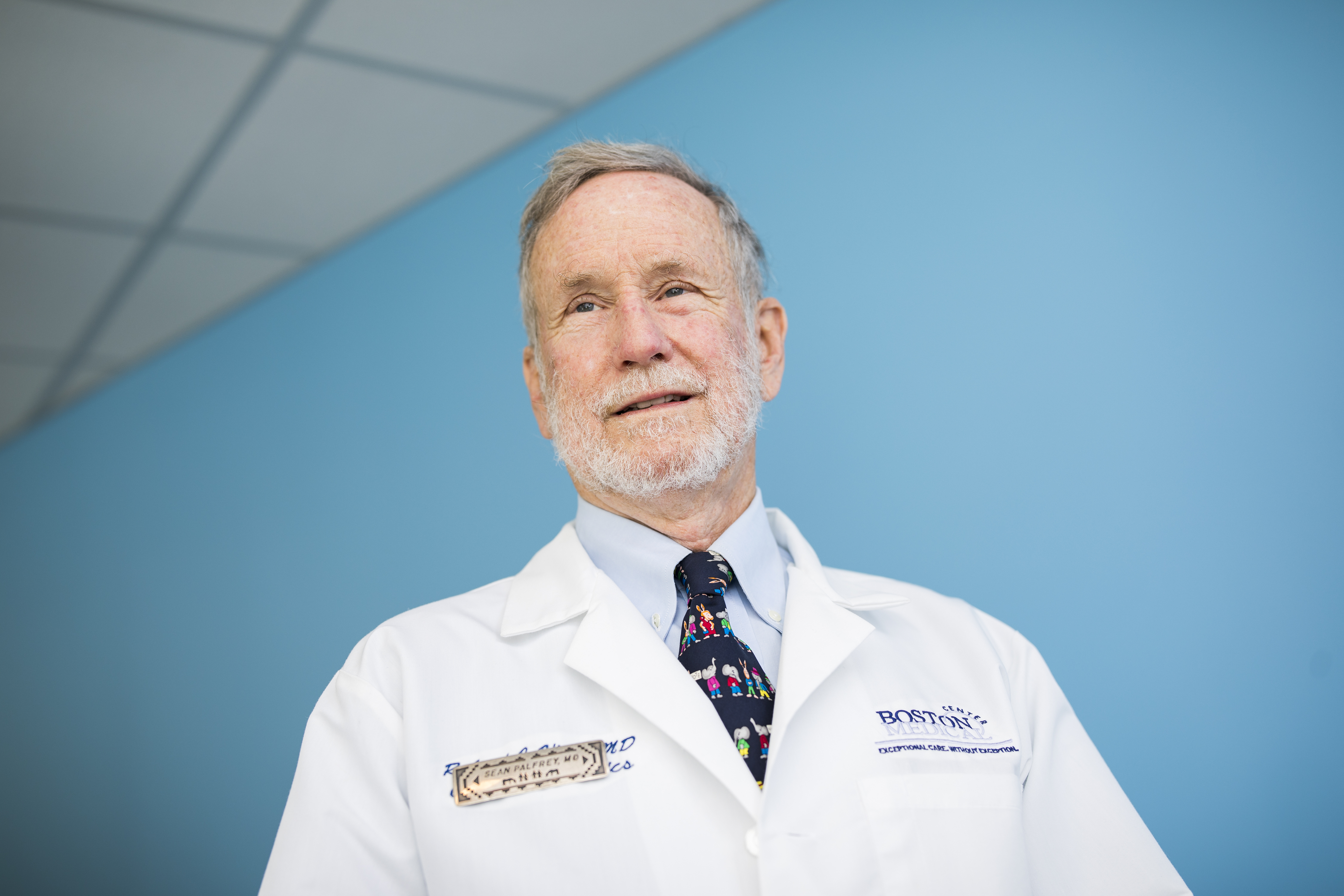

“People know about these diseases as mythic dragons. Years ago, you built castles and moats and city walls to keep those monsters out,” said Dr. Sean Palfrey, a pediatrician at Boston Medical Center, above. “We try not to terrify people, but if they're saying these things aren't important anymore, we have to remind them they're out there, and if we let down our guard, they will break in and maul us.”

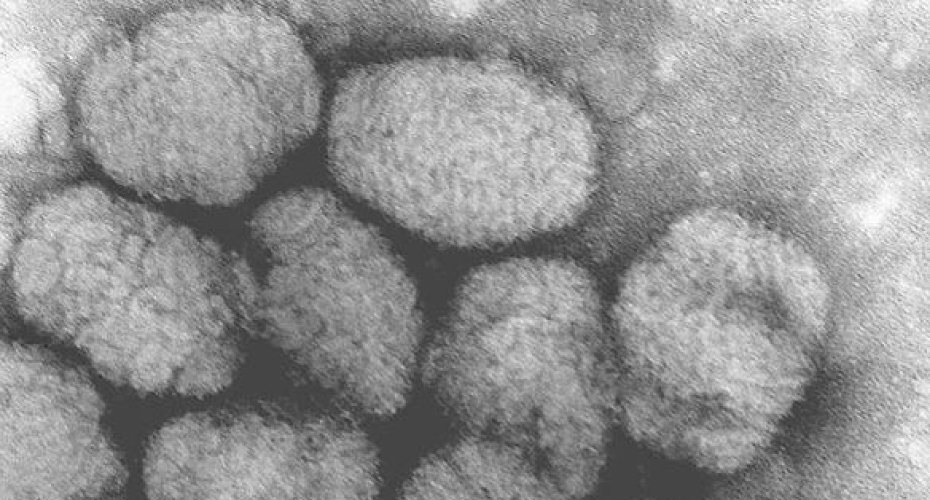

Coverage spoke with clinicians and loved ones of those who suffered from illnesses that vaccines have since made rare, including measles, polio, meningitis B and smallpox (the virus is seen in a magnified image above). Their words offer a powerful reminder of the vital importance of vaccination.

Learn more about how vaccines work

The vaccines we take for granted today were all public health breakthroughs, protecting us from potentially deadly diseases that once claimed lives by the millions. And it all started with the smallpox vaccine, developed in the late 1700s and used widely by the 19th century.

Prior to this, the disease wiped out entire populations. An estimated 4 million Aztecs died from smallpox. In the early 1700s, half of Boston’s 10,000 people were infected, and 800 died. About 300 million people have been killed by the disease.

“It was a horrific illness,” said Dr. Scott Podolsky, professor of global health and social medicine, and medical historian at Harvard Medical School. “It was both a lethal illness and highly contagious. And it left people terribly scarred.”

The disease caused high fever, aches and a deep rash, according to the World Health Organization. The rash would start out as flat red bumps, which over time would raise, blister and scab, leaving disfiguring pockmarks. The rash would usually begin in the mouth and throat before spreading to the face, arms, torso and legs. About 30 percent of people infected with the disease died.

Thanks to the vaccine, the disease was officially declared eradicated in 1979, a giant public health accomplishment.

“Initially, people were skeptical of the vaccine,” Podolsky said. “But it became a demonstration of how to eradicate a disease.”

Why I vaccinate my child

Five parents share their reasons for making sure their kids are protected against infectious diseases

More on “Live before vaccines” stories

Did you find this article informative? All Coverage content can be reprinted for free. Read more here.

PHOTO OF Dr. SEAN PALFREY BY NICOLAUS CZARNECKI, PHOTO OF Dr. SCOTT PODOLSKY BY FAITH NINIVAGGI